Home / Genus v. Species Patents: Obviousness, Evergreening, and Public Interest

Genus v. Species Patents: Obviousness, Evergreening, and Public Interest

- October 27, 2025

- Dhaneesha P B

The recent judgment of the Division Bench of the Delhi High Court in F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG & Anr. v. Natco Pharma Ltd. (FAO(OS) (COMM) 43/2025, dated October 9, 2025) examined the nuanced interplay between genus and species patents in the pharmaceutical sector.

The dispute involved the alleged infringement of Risdiplam, the active pharmaceutical ingredient claimed under the Plaintiffs’ (Roche and PTC Therapeutics Inc.) Indian patent IN 334397, titled “COMPOUNDS FOR TREATING SPINAL MUSCULAR ATROPHY” for treating spinal muscular atrophy.

This appeal arose from the refusal of an interim injunction by the Single Judge Bench of the Delhi High Court to restrain Natco Pharma Ltd. (Respondent) from manufacturing and selling Risdiplam, raising pivotal questions regarding patent infringement, novelty, inventive step, and the scope of genus versus species patents under Sections 64(1)(e) and 64(1)(f) of the Patents Act, 1970.

The case highlights the delicate balance between encouraging pharmaceutical innovation and ensuring prompt access to life-saving medicines, providing important insights on the scope and validity of genus and species patents while emphasising the courts’ role in preventing patent evergreening in the public interest.

The decision adds another dimension to India’s evolving jurisprudence on pharmaceutical patents post-Novartis v. Union of India, reaffirming judicial caution against incremental patenting.

Facts of the Case

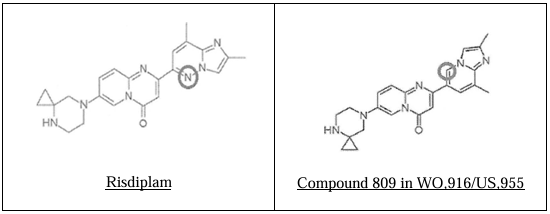

The suit patent IN 334397, a species patent, claiming Risdiplam for treating spinal muscular atrophy, is valid and set to expire on May 11, 2035. Natco Pharma Ltd. was manufacturing and selling Risdiplam, constituting prima facie infringement under Section 48(a) of the Patents Act. The respondent relied on Sections 64(1)(e) and 64(1)(f) to challenge the patent’s validity on grounds of lack of novelty and inventive step. The Single Judge Bench held that Risdiplam was obvious over prior art, specifically Compound 809 in the genus patent WO 2013/119916 (WO’916) and US 9,586,955 (US’955), as it differed only by substitution of a -CH group with a nitrogen (-N) atom, and fell within the Markush formulation disclosed in the prior patents. Consequently, the injunction against Natco was refused.

The chemical structures of Risdiplam and Compound 809 from WO‘916/US‘955 are as follows:

Observations of the Court:

Genus v. Species Patents & Coverage v. Disclosure

The Division Bench concurred with the Single Judge Bench’s observation that Risdiplam fell within the Markush formulation claimed in the genus patents WO‘916/US‘955. The Court referred to FMC Corporation v. Best Crop Science,[1] noting that mere coverage of a species patent compound within a genus patent’s broad Markush claim does not constitute disclosure unless the genus patent provides sufficient teaching to enable a skilled person to arrive at the species claim. The Court also referred to the decision in Astrazeneca AB v Intas Pharmaceuticals,[2] observing that if a defendant’s product allegedly infringes both the genus and species patents, it could be considered an admission of disclosure of the species claim in the genus patent.

While referring to Astrazeneca, the Court expressed reservations regarding the validity of the principle laid down by the Division Bench, emphasising the distinction that “infringement is predicated on coverage, whereas invalidity is predicated on disclosure.” The Court noted that any manufacture or sale by a defendant of a compound falling within the broad coverage of the Markush formulation in the genus patent would, by itself, entitle the holder of the genus patent to sue for infringement. However, Section 64(1)(e) would apply only if the claim in the species patent is actually disclosed in the genus patent. It is only if the product claimed in the species patent is specifically so disclosed or exemplified in the genus patent that it can be said that the claim in the species patent is disclosed in the genus patent. The Court stated that “infringement requires only coverage, whereas invalidity requires disclosure, and coverage by itself does not necessarily imply disclosure.”

Obviousness and Section 64(1)(f)

A claim is considered obvious if a person skilled in the art, relying on the disclosures of the genus patent and common general knowledge, could reasonably arrive at the invention claimed in the species patent.

The “Person in the Know” Test

The Court referred to Astrazeneca (DB), where it was held that when the inventors of the genus and species patents are the same, obviousness should be assessed from the perspective of the inventor, a “person in the know” rather than the usual “person skilled in the art.

In line with this, the Court observed that obviousness must be assessed by considering whether, based on the disclosures and teachings in the prior art genus patent, it would have been possible to arrive at the claim in the species patent. While this assessment is usually made from the perspective of a person skilled in the art, the paradigm shifts when the inventors of the genus and species patents are the same. What may be merely ‘obvious’ to a person skilled in the art would be even more apparent to the inventor of the genus patent, who is ‘in the know’ and fully aware of the intricacies and nuances of the genus patent.

Grimm’s Hydride Displacement Law and Bioisosterism

Bioisosteres are atoms or molecules that fit the broadest definition of isosteres and exhibit the same biological activity. In Grimm’s Hydride Displacement Law, N and CH appear in the same vertical column, indicating that they are bioisosteres—atoms with the same number of electrons and similar biological activity. Accordingly, the Division Bench agreed with the learned Single Judge that a person ‘in the know’, familiar with medicinal chemistry, would be readily motivated to substitute –CH with –N, thereby synthesising Risdiplam from Compound 809 in the genus patent.

Non-Exemplification of Risdiplam in the Genus Patent

For making out a prima facie case of obviousness, all that is to be seen is whether, from the disclosures which exist in the prior art, in the form of exemplified compounds or the teachings contained therein, a person skilled in the art would be able to reach the claim in the suit patent. Specific exemplification of the claim in the suit patent, in the complete specifications of the prior art document, is by no means necessary.

Evergreening of Patents and Public Interest

The purpose of the obviousness defence is to prevent evergreening, where a new patent is granted for merely obvious modifications of an existing invention. A patent grants exclusivity for 20 years, after which the invention becomes available to the public. The Court observed that “in the case of drugs and pharmaceutical products, this principle acquires a superadded and predominant element of public interest. If patents relating to essential and life-saving drugs are permitted to be evergreened, the drug may forever remain outside the public domain and available only for the original inventor to exploit, which could result in calamitous and incalculable public harm.”

The Court held that an inventor cannot extend patent exclusivity on essential or life-saving drugs through obvious modifications and claim them as “new” to gain a fresh patent term.

International References and Their Relevance

Disclosures in US PTE Application

The Court observed that the US PTE application and the Orange Book recitals do not, prima facie, show the suit patent’s invalidity under Section 64(1)(e). As held by the Single Judge, mere coverage or claiming of Risdiplam in the genus patent does not amount to disclosure, which is required for Section 64(1)(e) to apply.

The US Orange Book

The US Orange Book contains a disclaimer stating that users should not rely on its listings to determine enforceable patent claims, which undermines its reliability as evidence of invalidity under Section 64(1)(e). Similarly, the USPTO–FDA communication merely noted that Risdiplam is covered by US‘955, which alone does not establish a prima facie case of invalidity.

Court’s Conclusion

The Division Bench of the Delhi High Court upheld the decision of the Single Judge Bench rejecting the plea seeking interim injunction. A subsequent special leave petition filed before the Supreme Court was also dismissed on October 17, 2025. The main suit remains pending before the Single Judge Bench.

Final Thoughts

The Delhi High Court’s judgment underscores the nuanced distinction between coverage and disclosure in genus and species patents, affirming that mere inclusion of a species within the scope of a genus patent does not automatically render the species patent invalid. The Court evaluated obviousness from the perspective of a “person in the know,” particularly where the same inventors are involved in both genus and species patents.

Notably, the Court emphasised the public interest aspect, cautioning against the evergreening of life-saving drugs and reiterating that patent law must strike a careful balance between incentivising innovation and ensuring timely access to essential medicines.

The decision, therefore, not only clarifies the legal principles governing genus and species patents but also underscores the imperative of safeguarding public health in the pharmaceutical sector.

The Delhi High Court’s judgment underscores the nuanced distinction between coverage and disclosure in genus and species patents, affirming that mere inclusion of a species within the scope of a genus patent does not automatically render the species patent invalid. The Court evaluated obviousness from the perspective of a “person in the know,” particularly where the same inventors are involved in both genus and species patents.